Why We Were The Only Camper Van On Santorini Island

If I’d written a list of all the least likely places we would take our van, Santorini would’ve been in the top ten. Probably alongside places like Greenland and Gaza. Yet in September 2021 we somehow found ourselves on a ferry to this most famous of Greek Islands, our van parked below deck, feeling somewhat queasy at the speed our boat was whizzing from island to island. Not one person on that ferry was badly dressed; everyone was sporting sun hats and designer Polo shirts, positively dripping with laidback Mediterranean vibes. Then there was us, with our three day old outfits and dirty feet, snoozing in the recliner seats and occasionally jumping up to capture a video as we docked at another island.

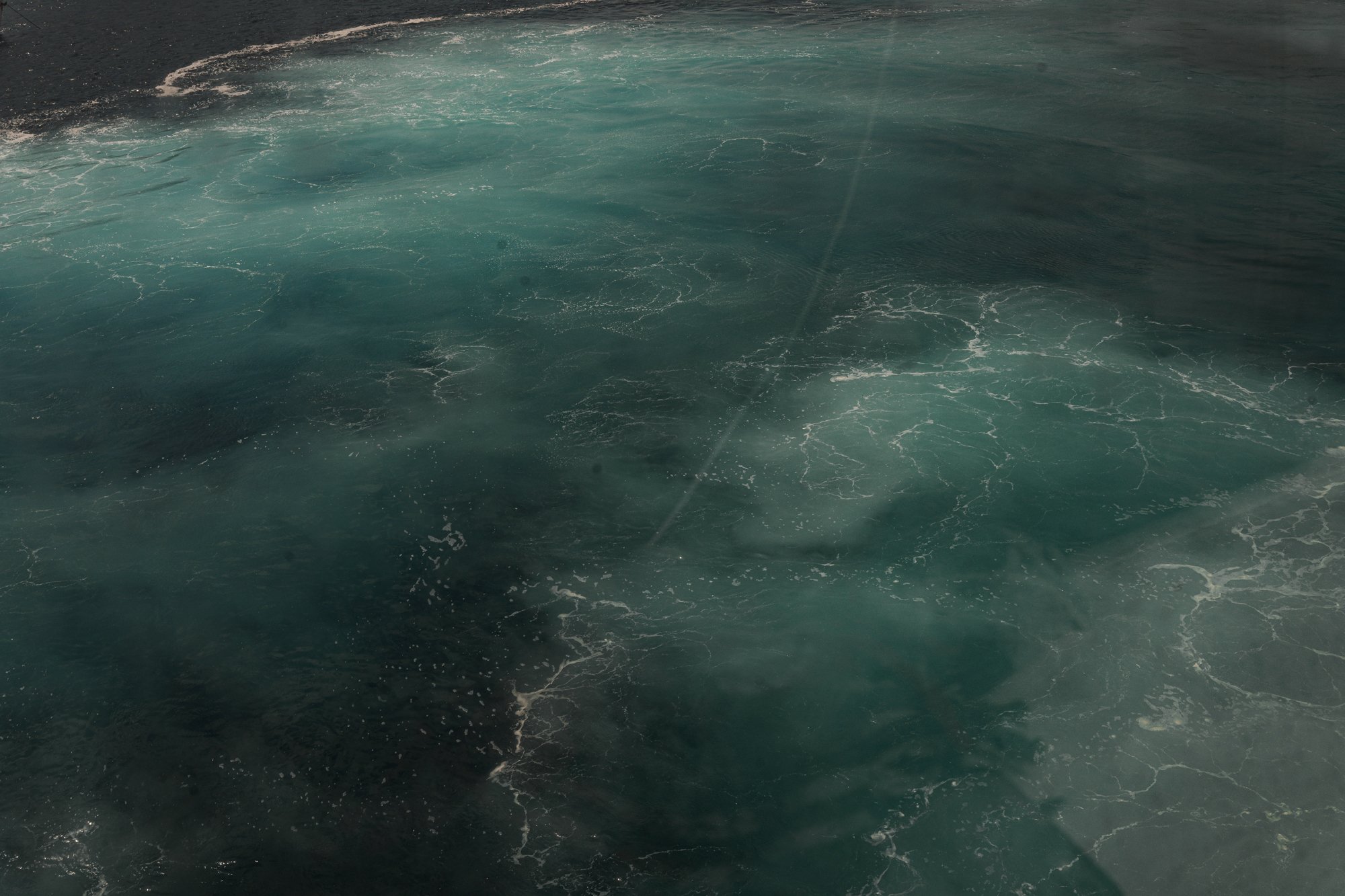

When our producer had put forward the first draft of a route plan around Europe for the TV program we were making, we were surprised to see Santorini on there as the final destination. We knew nothing about the place, apart from the fact that Greek islands were usually reserved for wealthy tourists and the elite; we were neither. But our producer had seen an opportunity to film at possibly one of the most far-flung hot springs in all of Europe, and wanted the final shots of the programme to be of us waving goodbye to our adventure, illuminated by the glow of one of Santorini’s famous sunsets. We were keen, especially as they’d be paying for the ferry.

Disembarking at the port of Thera after a 5 hour journey, running on very little sleep having risen at 4am to drive to Athens and board, to be faced with a near-vertical zigzag road up a cliff face teeming with cars, coaches and quad bikes, was more than our sleep-deprived brains could handle. Buses swung around the tight corners with careless abandon, quads and mopeds wove in and out of the traffic, and not one junction on the island seemed to have any road markings; you just went when you could, foot on the accelerator, eyes closed. It was busier than St Ives back home in peak summer.

Then there was the ordeal of trying to find somewhere to park for the night. The beaches were either too wild to access or completely overcrowded. Several of them were under the direct flight path of the island’s one and only airport (“how many planes can there really be?” I’d asked, before realising pretty soon they took off approximately four an hour).

We settled for the first night slightly inland at a beautifully quintessential Santorini church, blue and white with a domed roof overlooking a panoramic sea view. We thought we’d struck gold, until the wind picked up in the evening and didn’t stop until it was blowing handfuls of dust into our van and slamming the side door on its roller to the point we thought it might break. In fact this wind didn’t cease for one single moment until we left the island, an ever-present annoyance that rocked our van all night and forbid us even one peaceful night’s sleep.

We could see why we were the only campervan on the island; there were far better-equipped islands that were cheaper and easier to reach, and ones which most likely had water sources, unlike this one. If it hadn’t been for washing in the extremely salty sea and a kind hotel owner who let us fill up our tanks from his hose, we would’ve run dry in a matter of days.

As an interesting side note, we learned that there are no water sources on Santorini. Your options as a resident are to either pay extortionate water rates to a company which desalinates and distributes water from the sea, or dig your own borehole (also expensive). All of the drinking water on the island, whether it’s in hotels, restaurants or supermarkets, is bottled, which in our view makes Santorini quite an environmental disaster. Or rather brings it on par with the rest of the Balkans in terms of ecological awareness.

We spent the next few nights of our stay at a sort of nowhere beach; at the end of a residential street, next to a beautiful abandoned chapel, we spent four nights being blasted by salt and dusty wind. Each morning we had to clean the sea spray off our windows before we could drive, and the salt was not doing our rusty van any favours.

Most everything on Santorini was covered in a layer of dust; we spent much of our time in car parks trying to one up each other in finding the dustiest car. We couldn’t be sure if they’d been abandoned for days or months, such was the amount of dust which flew through the air, getting into your hair, your clothes and every fibre of your being.

It was little wonder most people rented a quad bike, dune buggy or smart car to get around the island, as the roads were remarkably narrow and windy. Not impossible in a van, especially with two drivers from Cornwall at the wheel, but narrow enough to make driving daily a bit of a chore. And parking anywhere in Thira or Oia? Forget about it.

If we hadn’t been standing dutifully by our van as one of Oia’s many car parks filled up around us we would’ve quickly been blocked in by brainless tourists, who had to be told in no uncertain terms not to park right in front of our bumper.

As a couple of travellers who spend their lives seeking out the most remote and least-visited places in Europe, and eventually Planet Earth, walking around Oia was nothing short of unbearable.

Overpriced tourist shops assaulted you from every angle; restaurants boasted two-figure dishes and three-figure bottles of wine; everyone was dressed to the nines and girls were walking around in flying dresses and queueing to take their selfies at the most Instagrammable spots.

If you’d ever Googled Santorini then the photos you would’ve seen were undoubtedly taken in Oia, which boasts over 70 domed churches and whitewashed Cycladic houses oozing down the cliffside, interspersed with narrow, windy stairs and private swimming pools. It is, undoubtedly, one of the most beautiful sights in Greece, built on the steep slope of the volcanic caldera above the old fishing port of Ammoudi, and its idyllic scenery has captured the imaginations of many a wanderluster, as it captures the hearts of its 2 million annual visitors. But Santorini has become a victim of its own success, as the local authority was forced to begin limiting numbers of arrivals in 2019 due to the strain the large numbers of tourists were putting on local services, threatening the delicate ecology of the island. Needless to say, this was not a statistic we felt comfortable being a part of.

After an hour of being paraded around for the cameras and pretending to enjoy ourselves we simply couldn’t wait to leave. The only saving grace of Oia for us was an adorable little family-run souvenir shop where we spoke to one of the shopkeepers and purchased a big blue glass Eye of the Gods to take home.

The Eye of the Gods is a symbol you will see throughout the island of Santorini and across mainland Greece too, hanging in the doorways of shops, above the counters of restaurants, on boats and on car keys. The Eye is meant to ward off the evil energy that can be passed from one person to another through bad thoughts or words, or more broadly it is believed to protect against misfortune.

Our producer bought each member of the crew a small Eye which Ben and I keep on our keyring, while another hangs in the cab of our van. We made it the whole 2,500 miles back to Cornwall without a single breakdown, so perhaps the Eyes brought us good fortune after all.

Admittedly I became a little obsessed with the Eye in our time on Santorini, as I did with the most peculiar way in which they grow their grapes. Instead of the tall, pinned-up grape vines you see in the vineyards of Italy and France, the vines on Santorini are grown low to the ground in the shape of a basket. This is to protect them from the wind, but what is also unique are the varieties of grape which thrive in the island’s volcanic soil known as Assyrtiko.

While we’re not big wine drinkers I did become a little enamoured with the vine baskets people were displaying on walls and mantels, and on our last day on the island I came across a huge stack of vines, presumably to be used as firewood, of which a few were still in the shape of baskets. I asked a cute little old lady who came out of the house opposite if I could take one, to which she obliged, unknowingly making my day.

I held my hand up to my chest to say thank you, being careful not to wave or give her a thumbs up, both of which are, rather confusingly, insults in Greece.

In sharp contrast to Oia’s overcrowded, over-Instagrammed streets, the traditional settlement of Megalochori provided us with a breath of fresh air. Wonderfully uncrowded and refreshingly laidback, we spent our last day on the island here photographing its pretty streets, tiered church bell towers and charming doorways. We got the chance to experience some of the most ancient music in Greece at Symposion which we would thoroughly recommend to anyone visiting Santorini and wishing to escape the cultural vacuum. We’ve dedicated an entire blog post to Symposion and Megalochori which you can read here.

After a whole week of filming, sailing to remote hot springs and driving around in dusty circles on the island, our time in this far flung corner of Europe was over. We spent one last night camping on the relentlessly windy cliffs to enjoy a beer and a Cornish cider at sunset, before jetting back off to the mainland to begin our adventure home.

For the second time we were accosted by the ferry staff who said that our €313 ferry ticket for a vehicle over 5m was not sufficient, and demanded we pay extra. The producer had covered the cost on the outbound journey after the staff took Ben’s passport hostage and refused to let us board until it was paid, but Ben was summoned to the reception this time to make the payment upfront: a whole €16 extra.

Such was the impatience of the Greeks that they attempted to board everybody at the same moment in order to disembark as quickly as possible. Dozens of cars and thousands of suitcase-wielding passengers boarded the ferry in droves as the staff shouted orders and indicated for us to board too (if we could’ve spoken Greek we imagine it would’ve been something like “Go! Go! Go! Go! Go!”). We soon found ourselves trapped in a swarm of predominantly American tourists trying to shove their baggage onto racks, and by the time the dust settled the boat had already lifted its ramp and set sail, which made driving inside the hull to our parking space a pretty sickening experience.

Our time on Santorini had been a transformative experience in more ways than one. On day one we’d felt overwhelmed by the claustrophobia of people; by day seven that had changed very little, but through the wonderful characters we’d been introduced to and the time spent honing our knowledge of this small yet richly cultured island, we’d begun to develop a true appreciation for the uniqueness of Santorini.

Would we return in a van?

Most probably not.

The story of how we took the most unlikely van to the furthest Western point of Europe– the Azores islands.